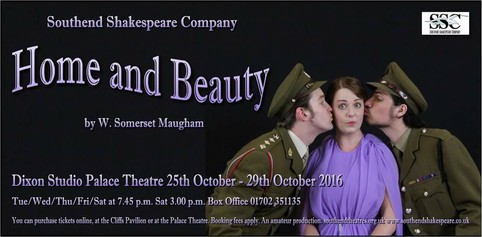

Home and Beauty

Southend Shakespeare Company

Dixon Studio, Palace Theatre, Westcliff on Sea

25th-29th October 2016

7.45pm

Southend Shakespeare Company

Dixon Studio, Palace Theatre, Westcliff on Sea

25th-29th October 2016

7.45pm

EMERGING like a theatrical ghost from the depths of an almost forgotten era, Home and Beauty is a real discovery.

Somerset Maugham's social comedy, revived and splendidly staged by Southend Shakespeare Company, looks at first sight like a bit of stage candyfloss.

Superficially, it is about a love-triangle situation in which a society beauty finds herself married to two men at the same time. At first glance, it looks like just another of the sort of fluffy concoctions that packed in West End audiences in 1919, when Home and Beauty was first produced. The tensions, subterfuges and comic twists, developed via the medium of Maugham's witty dialogue, guaranteed a great night out.

Perhaps surprisingly, they still guarantee a great night out. Home and Beauty is clearly a period piece, but it has not really dated. Much of the most effective comedy comes from the empty-headed central character, Victoria. Essentially a bimbo in couture, she is a timeless figure. Victoria is deliciously played by Alice Ryan.

It is typical of Victoria that she regards the carnage of the First World War as a source of personal inconvenience. “When my first husband was killed,” she complains, “my bust went to nothing. I couldn't wear a low dress for months.”

Frivolity like this keeps the play merrily rolling along for two hours. Yet beneath this seemingly unchallenging veneer, lies a far more heavyweight play.

Home and Beauty opens a window onto post WW1 society. The terrible conflict is over, yet the reverberations continue. We are used to works like Journey's End and which depict the horrors and absurdities of conflict. Home and Beauty is about the aftermath. Maugham makes great play with the materialistic aspects of 1919 life. For instance, there is coal rationing. The shortage of fuel means that Victoria has entrenched herself in her bedroom, allowing a giant, and heavily symbolic double-bed to occupy centre stage.

One of the most cherishable scenes in recent Southend theatre comes from a brief cameo by Sue Morley. She plays a domineering cook, who unlike Victoria and her husbands, is wealthy enough to own her own car . Such is the shortage of domestic staff (“It's harder to get a parlour maid than a peerage,” notes Victoria) that the so-called ruling classes meekly comply with her every demand. Some posh blokes are even marrying their cooks to ensure a modicum of domestic comfort.

Mood-wise, the play distills the sense of cynicism and shallow hedonism which prevailed following the bloodshed and loss of the Great War. Victoria's first husband, William (Ben Smerdon), is listed as dead at Ypres. He returns, very much alive, to reclaim his wife, only to find her married to his best friend, Frederick (Elliot Bigden).

The cynical twist comes from the fact that both William and Ben view this situation as a way to escape from Victoria's shackles – while they hypocritically pretend to sacrifice their love in a spirit of self-denying nobility.

Bigden and Smerdon are both brilliant as the competing soldier husbands. Bigden is particularly effective in the way he commands the role of an idle, bed-feathering, staff officer – a type regarded as a bigger enemy than the Germans by the fighting soldiers on the Western Front (Tim McInnerny played a similar character in Blackadder Goes Forth). The degeneration of their friendship, as they battle to be Victoria's ex, is great fun to watch. But the undercurrent of anguish is convincingly delivered by both these young actors.

Just when the fun might threaten to flag, along come two intriguing new characters, played with infectious relish by Keith Chanter and Zoe Berry. Mr Raham is London's most successful divorce lawyer, revelling in the mass post-war marital scene, where husband and wife break-ups match the trenches in terms of the scale of carnage. Miss Montmorency is a professional femme fatale, hired to provide legal grounds for divorce. She turns out to be surprisingly prim 'n proper.

Ross Norman-Clarke is also in hilarious form as the wealthy industrialist on whom Victoria sets her sights to fill the role of husband No3. This is a man who has grown fat and smug on the proceeds of war, and other men's blood, so, again, there is a darker presence beneath this simpering, lovelorn twit.

Director Jacquee Storozynski-Toll makes ingenious use of the compact Dixon Studio space, mounting the production on two separate levels. Relationships which begin upstairs in the bedroom, terminate around the dining-room table – a good visual metaphor for the play as a whole.

Home and Beauty can be enjoyed simply as a witty social comedy in the tradition of Oscar Wilde (and Noel Coward regarded Somerset Maugham as something of a guru). But at a different level, it will also appeal to anyone with an interest in history as it was lived. Despite the laughter, Home and Beauty almost qualifies as a neo-realist play.

Home and Beauty

Palace Theatre (Dixon Studio), Westcliff

Nightly at 7.45 until Sat Oct 29

Tickets 01702 351135 www.southendtheatres.org.uk

Somerset Maugham's social comedy, revived and splendidly staged by Southend Shakespeare Company, looks at first sight like a bit of stage candyfloss.

Superficially, it is about a love-triangle situation in which a society beauty finds herself married to two men at the same time. At first glance, it looks like just another of the sort of fluffy concoctions that packed in West End audiences in 1919, when Home and Beauty was first produced. The tensions, subterfuges and comic twists, developed via the medium of Maugham's witty dialogue, guaranteed a great night out.

Perhaps surprisingly, they still guarantee a great night out. Home and Beauty is clearly a period piece, but it has not really dated. Much of the most effective comedy comes from the empty-headed central character, Victoria. Essentially a bimbo in couture, she is a timeless figure. Victoria is deliciously played by Alice Ryan.

It is typical of Victoria that she regards the carnage of the First World War as a source of personal inconvenience. “When my first husband was killed,” she complains, “my bust went to nothing. I couldn't wear a low dress for months.”

Frivolity like this keeps the play merrily rolling along for two hours. Yet beneath this seemingly unchallenging veneer, lies a far more heavyweight play.

Home and Beauty opens a window onto post WW1 society. The terrible conflict is over, yet the reverberations continue. We are used to works like Journey's End and which depict the horrors and absurdities of conflict. Home and Beauty is about the aftermath. Maugham makes great play with the materialistic aspects of 1919 life. For instance, there is coal rationing. The shortage of fuel means that Victoria has entrenched herself in her bedroom, allowing a giant, and heavily symbolic double-bed to occupy centre stage.

One of the most cherishable scenes in recent Southend theatre comes from a brief cameo by Sue Morley. She plays a domineering cook, who unlike Victoria and her husbands, is wealthy enough to own her own car . Such is the shortage of domestic staff (“It's harder to get a parlour maid than a peerage,” notes Victoria) that the so-called ruling classes meekly comply with her every demand. Some posh blokes are even marrying their cooks to ensure a modicum of domestic comfort.

Mood-wise, the play distills the sense of cynicism and shallow hedonism which prevailed following the bloodshed and loss of the Great War. Victoria's first husband, William (Ben Smerdon), is listed as dead at Ypres. He returns, very much alive, to reclaim his wife, only to find her married to his best friend, Frederick (Elliot Bigden).

The cynical twist comes from the fact that both William and Ben view this situation as a way to escape from Victoria's shackles – while they hypocritically pretend to sacrifice their love in a spirit of self-denying nobility.

Bigden and Smerdon are both brilliant as the competing soldier husbands. Bigden is particularly effective in the way he commands the role of an idle, bed-feathering, staff officer – a type regarded as a bigger enemy than the Germans by the fighting soldiers on the Western Front (Tim McInnerny played a similar character in Blackadder Goes Forth). The degeneration of their friendship, as they battle to be Victoria's ex, is great fun to watch. But the undercurrent of anguish is convincingly delivered by both these young actors.

Just when the fun might threaten to flag, along come two intriguing new characters, played with infectious relish by Keith Chanter and Zoe Berry. Mr Raham is London's most successful divorce lawyer, revelling in the mass post-war marital scene, where husband and wife break-ups match the trenches in terms of the scale of carnage. Miss Montmorency is a professional femme fatale, hired to provide legal grounds for divorce. She turns out to be surprisingly prim 'n proper.

Ross Norman-Clarke is also in hilarious form as the wealthy industrialist on whom Victoria sets her sights to fill the role of husband No3. This is a man who has grown fat and smug on the proceeds of war, and other men's blood, so, again, there is a darker presence beneath this simpering, lovelorn twit.

Director Jacquee Storozynski-Toll makes ingenious use of the compact Dixon Studio space, mounting the production on two separate levels. Relationships which begin upstairs in the bedroom, terminate around the dining-room table – a good visual metaphor for the play as a whole.

Home and Beauty can be enjoyed simply as a witty social comedy in the tradition of Oscar Wilde (and Noel Coward regarded Somerset Maugham as something of a guru). But at a different level, it will also appeal to anyone with an interest in history as it was lived. Despite the laughter, Home and Beauty almost qualifies as a neo-realist play.

Home and Beauty

Palace Theatre (Dixon Studio), Westcliff

Nightly at 7.45 until Sat Oct 29

Tickets 01702 351135 www.southendtheatres.org.uk

Tom King 27/10/2016